- Home

- Carney Vaughan

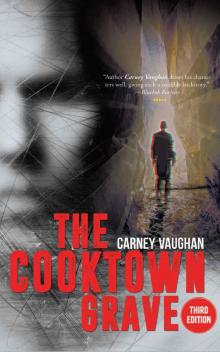

The Cooktown Grave

The Cooktown Grave Read online

Copyright © 2020 Carney Vaughan.

978-1-955575-02-7 - EBook

978-1-955575-03-4 - Paperback

978-1-7343844-5-1 - Hardback

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means—whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law.

Prepared for publication by:

Authoraide Publications, LLC

1603 Capitol Ave, Suite 310 A275 Cheyenne, Wyoming 82001

Office: (307) 459-1803 | Fax: (307) 224-8450

Website: www.authoraide.com

Contents

PART ONE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Part Two

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

PART THREE

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Chapter 85

PART ONE

CHAPTER

1

For the first few days in port Mac would find himself confined to the Monterey Star, prisoner of the many repair jobs generated by constant ocean forces and corrosive effects of saltwater. His time became his own when the trawler was again shipshape. The skipper when satisfied would take the Star back down Trinity Channel and out again to sea.

But on his first free day Mac would lift the trawler’s trail-bike from the hold onto the dock. After converting his cheque into cash, he would leave the Cairns waterfront and head northwards on Sheridan Street. On the outskirts of the city proper Sheridan Street gives up and becomes Captain Cook Highway. Just before Smithfield Heights the Highway’s right fork would take Mac up the cape towards Port Douglas on Route 44. The left fork continues on as the national Route 1 where it becomes the Kennedy Highway and wends its way up the seaward face of the Great Dividing Range. Route 1 serves Kuranda and the table-lands and then moves on toward the Gulf of Carpentaria, and beyond.

About eleven o’clock on this morning the signposted turnoff to Port Douglas slipped by and signalled fourteen kilometres to Mossman. On the prior outskirts of that town Mac took a left and headed inland, southwest to Mount Molloy along a gently undulating ribbon of bitumen. The road forms one border of the many cane fields, orchards and tea plantations that dot the rich soil of this coastal plain. About a kilometre north of Mount Molloy he turned right onto the Peninsula Development Road and gave the Yamaha some stick. Mac had travelled this route many times and he knew he had seventy-five kilometres of excellent sealed road in front of him. As long as the stray cattle and the wildlife were nervous enough to respond to the racket of the bike’s open exhaust he knew he could make up time along this stretch. Less than a quarter of an hour later he watched the pit-head machinery of the Mount Carbine mine slide by.

The end of the bitumen meant another ten kilometres to the Palmer River. Mac stopped there for fuel and coffee and a bunch of flowers that was stuffed into a saddlebag. Some thirty kilometres further on he passed the Lakeland Roadhouse. He alternated his pit stops between these two general stores and if there were no fresh flowers, he would scout the passing terrain for wildflowers.

Lakeland, as a milestone, always told him there was another eighty odd kilometres of dirt road between the Yamaha and Cooktown. If he was lucky the shire’s road grader would have it in a reasonable condition.

Mac was lucky!

Soon after he was through the Black Mountain national park and rattling the planks of the long, single lane wooden bridge across the Annan River. It was just three hours after leaving the National Bank in Cairns that Mac was kneeling beside a sealed grave of white marble and limestone chip gravel. A monument, near the Chinese shrine, in the Cooktown cemetery. A local would have wondered why he made these regular trips to their graveyard hence the flowers which, after their ordeal in the saddlebag, were always a bit ratty. But because it is an offering on a scale somewhere between a necessary subterfuge and an expression of total love, a person will always be forgiven the condition of a bunch of flowers. It usually signals the token surrender of all hostile sentiments, but only the giver knows its intent, and only the recipient can judge its worth. In this instance the flowers were a perfect cover for Mac’s mission.

He placed the flowers at the head of the grave, joined his hands and bowed slightly as if in silent prayer. A keen observer would have to be very close to see there was nothing devout going on here, but that Mac’s hooded eyes were scanning the precincts for anyone close enough to make out what he was about to do. Satisfied, he took two pieces of thin flat metal from his hip pocket. He slipped these under each end of a small slab of marble which served as a sort of keystone at the base of the large white crucifix. After it was removed, it allowed him to remove two larger pieces which exposed a cavity of considerable proportions inside the base of the cross.

At this point Mac always wondered, about the integrity of the stone-mason, and whether the bereft thought they were getting a solid marble cross.

From the cavity he withdrew a Tupperware double-loaf bread container as heavy as two phone books. When the lid was removed a couple of one-hundred-dollar bills, which had clung to it, fell among the flowers. Mac scooped them up and glanced around to reassure himself nobody was

within sight. He placed them, along with a bundle he took from his jacket pocket, back into the bread container. It was already bulging and wouldn’t accept much more. By his rough accounting Mac calculated there was about a-hundred-and-fifty-thousand-dollars in it. He reversed the dismantling procedure and soon the masonry was restored to its seemingly untouched condition. He stood and made an ostentatious sign of the cross and then bent to pull some weeds which had struggled up through the white gravel, no doubt the product of seeds in the droppings of some passing bird. His aim in grooming was to keep the grave from becoming apparently derelict. Its neatness, he reasoned, would save it from too-close scrutiny by do-gooders. So far it seemed to have worked.

On the way back to Cairns Mac felt an inner calm as he always did. On the way north to the cemetery the uncomfortable butterflies of apprehension were always present. Maybe workmen, or possibly vandals, had discovered his hiding place. But it was the tenth year now and after some thirty-odd trips it still seemed as secure as in the beginning.

He should be back in Cairns by five in the afternoon at the latest. As he stared at the road ahead a part of Mac’s mind travelled back in time, ten years in time, to his first visit to the Cooktown cemetery…

It was two months after he left Sydney that he’d arrived in Cairns. The transport driver who had picked him up at McDonald’s restaurant at the northern end of Parramatta, set him down in the main street of Coff’s Harbour. With a wink the truckie said, “Look after yerself son.”

Mac had been flat broke except for the ten dollars the driver had thrust into his palm as they shook hands. His flushed face was mistaken for the embarrassment of charity by the truckie who said, “Don’t worry about it son, just pass it on to some one else when yer got it to spare.” His face was burning, he knew it was red. But his embarrassment was caused by the guilt he felt. Under his stolen jacket he held a pair of rolled up jeans he’d pinched from behind the seat in the prime mover.

He tracked down a public toilet and, in a cubicle, took off his prison trousers and pulled on the jeans.

His conscience cleared.

The two knees were missing and there was a hole worn in the backside. They were covered in grease and dried mud. No doubt they were part of the truckie’s working gear and very near to their death through rough use and old age. He felt a little more secure then as the only prison garb he had on was the shirt hidden under his jacket. His joggers were his own; they were part of his pre-prison wardrobe. He rolled up the offending trousers and bundled them inside his jacket. But when he stepped out into sunshine he felt as conspicuous as a bandaged thumb.

Gravitating towards the waterfront he stopped to pick up a coffee and a hamburger on the way. At the beach he found a picnic table where he sat and contemplated his future. Where would he go? What would he do? How would he live? He was a fugitive.

He was looking, without seeing, at two men on the deck at the sharp end of a fishing boat moored some distance off the beach. They worked over a piece of machinery and then disappeared from view. It wasn’t until he heard the grind of coarse sand under the keel of an aluminium dinghy that he realised they were there in front of him. One of them dragged the runabout up the beach past high water mark and set the pick in the sand. The other cradled a heavy looking cylindrical object in his arms, he was rejoined by the first and together they walked past the table. One said “‘Scuse me, mate, could you keep an eye on our dinghy while yer sittin’ there? We won’t be long.”

“Sure,” he replied.

It was almost dark when they returned and the other one was carrying the burden. “Shit! Sorry mate. We didn’t think we’d take this long. We couldn’t get it fixed anyway.”

“What’s wrong?”

“It’s our anchor winch, it’s dead. We got a crank handle but, Christ, when yer in forty t’ fifty fathoms it seems to take all day. And it’s bloody hard yakka.”

“If it’s not burnt out, I can fix it.”

They looked at each other and one said “It don’t smell like it’s burnt out. What’s yer name?”

Quick! What? “McDonald’s…,” he mumbled. “…Mac,” and at that moment he became Mac and began his association with the sea. By the time he arrived in Cairns he was just another body occupying space in a tough industry which judged a person not by their past but their immediate performance. And they came down heavily on anyone who screwed up...

Ten years had passed since that first visit to the Cooktown grave and, as always during his return journey to the trawler, Mac was reliving it.

He had found the grave by chance. On his first trip to work Banana prawns in the Gulf of Carpentaria the region was yielding its usual bounty. Mac’s boat was right up there among the top scorers when the aggregates where tallied. It was threatening the minor premier when the main winch gave up the struggle. The diesel engine which powered it, seized. That meant, at least, a two-hundred-kilometre trip from Weipa up the western side of Cape York Peninsula to Thursday Island for repairs. On TI the lack of spares then meant parts would have to be sent up from Cairns. The fishing season in the Gulf was near its end and would probably be finished by the time repairs were completed. The skipper filled the tanks with fuel and they set off down Endeavour Strait towards Cape York and Cairns.

In the Strait, defying reports of a sudden barometric low out in the Coral Sea, they pressed on. But after rounding Cape York the weather turned foul as the low degenerated into a rain depression. A further hundred kilometres into the journey, as conditions worsened, signs of an unseasonable tropical cyclone loomed. They could have sheltered at Portland Roads but decided to plough on. Just short of Cooktown they were in real danger of foundering. It’s a toss-up whether they powered up the Endeavour River or were blown there. Depends who tells the story.

Mac had eight thousand dollars due. He asked the skipper to hold three for safe keeping. He took five thousand, quite a wad, and it was then, because he couldn’t bank his money, the need for a safe hiding place became urgent. It had to be a place which would be accessible at all times, day or night.

On a visit to the local cemetery during one of his many hikes around the Cooktown district while the weather was blowing itself out, Mac got an idea. He came back that night to what was more of a tourist attraction than a real cemetery and he brought with him his cash. He also brought some tools and, importantly, the galley’s bread container, not because he had visions of amassing a fortune over the ensuing years and would need something of that size. He brought it because it was sealable.

Back on the boat someone asked, “Where’s our breadbox?” “Must’ve gone over the side in the storm,” Mac answered. “S’ funny. Bread’s still here.”

Mac didn’t respond.

Up till now he’d been quite happy with its size but he would soon have to get something larger.

CHAPTER

2

On the Smith’s Creek dock alongside the Monterey Star Mac had little memory of the return trip. He slung the Yamaha on the block and tackle, swung it aboard and dropped it into the hold. He followed it down and secured it with ropes then climbed back on deck. A body was bent double, examining a new net which had just been delivered. He gave the ample, upthrust rump a slap and said. “I’m going uptown Reg. Do you want me to bring anything back?”

A pair of pale, once blue, sun bleached eyes turned on him. “No thanks, Mac. You want some tucker?”

“No. I’ll have something to eat up town, thanks Mate.”

Mac started his pub crawl as he always did, in the uptown, upmarket hotels. Then he would gradually work his way down the class ladder. His final mark was the gutter outside one of the waterfront bloodhouses. When there was no one left to talk with, Mac, with just the right amount of stagger, would wend his way back to the boat. Although he would buy a large number of beers, he would consume no more than three or four, the rest he would discreetly spill while listening to the scutt

lebutt. Mac’s plan never varied no matter which port he was visiting and he reasoned he heard most of the startling gossip which circulated on the entire east coast. In the beginning it had been a discipline but now it was a habit he enjoyed.

Tonight, though, was different.

They followed him from pub to pub, three of them, relentlessly, like jackals on injured prey. Never harassing, maintaining a distance. Just watching and waiting. He couldn’t pinpoint exactly where or when they tagged him but, suddenly, they were there. Mac knew he was in trouble but he couldn’t seek police help. They were with him as he left the public bar of the fashionable Hides Hotel and a genuine drunk would probably not have noticed them. He tried to shake them but one would tail him into a pub. The other two would wait outside, to pick him up again when he left. On any other night Mac would see familiar faces from the fishing fleet with whom he could link up, but tonight there was no one. Continuing the charade Mac wobbled up to the bar of the last pub on his mental list, desperately seeking a diversion. None was imminent.

“I’m sorry, I can’t serve ya, Love, ya drunk.” The barmaid recited the city ordinance in her own fashion. “Y’ avta leave or I gotta call the manager.” He turned away and staggered to the door leading to the loading dock in the side lane, lurching, colliding with other drinkers and tugging at the front of his trousers.

“Got ‘av piss,” he mumbled and stumbled through the doorway out into the dark delivery dock. They followed. For the first through the door the darkness exploded in a blinding flash. His nose was broken and he went down in a tangle of arms and legs. Mac shook his hand in pain, he decided to bolt.

There was no escape!

The wrought iron gates at the entrance to the loading dock were chained and padlocked. The adrenalin was coursing now and there was a trace of panic scattering his thoughts. The eyes of the others were given just enough time to adjust.

“The cunt’s not pissed, it’s bullshit. Watch out!” said the second, as he and the third, in a pincer movement, advanced on their prey. Mac, moving quickly backwards to prevent them from circling him, angled towards the junction of two walls. He wanted his back in a corner. He succeeded only in stumbling over number one threshing around on the ground, moaning and snorting blood.

The Cooktown Grave

The Cooktown Grave